- Tomasz Rydelek

Escape from isolation.

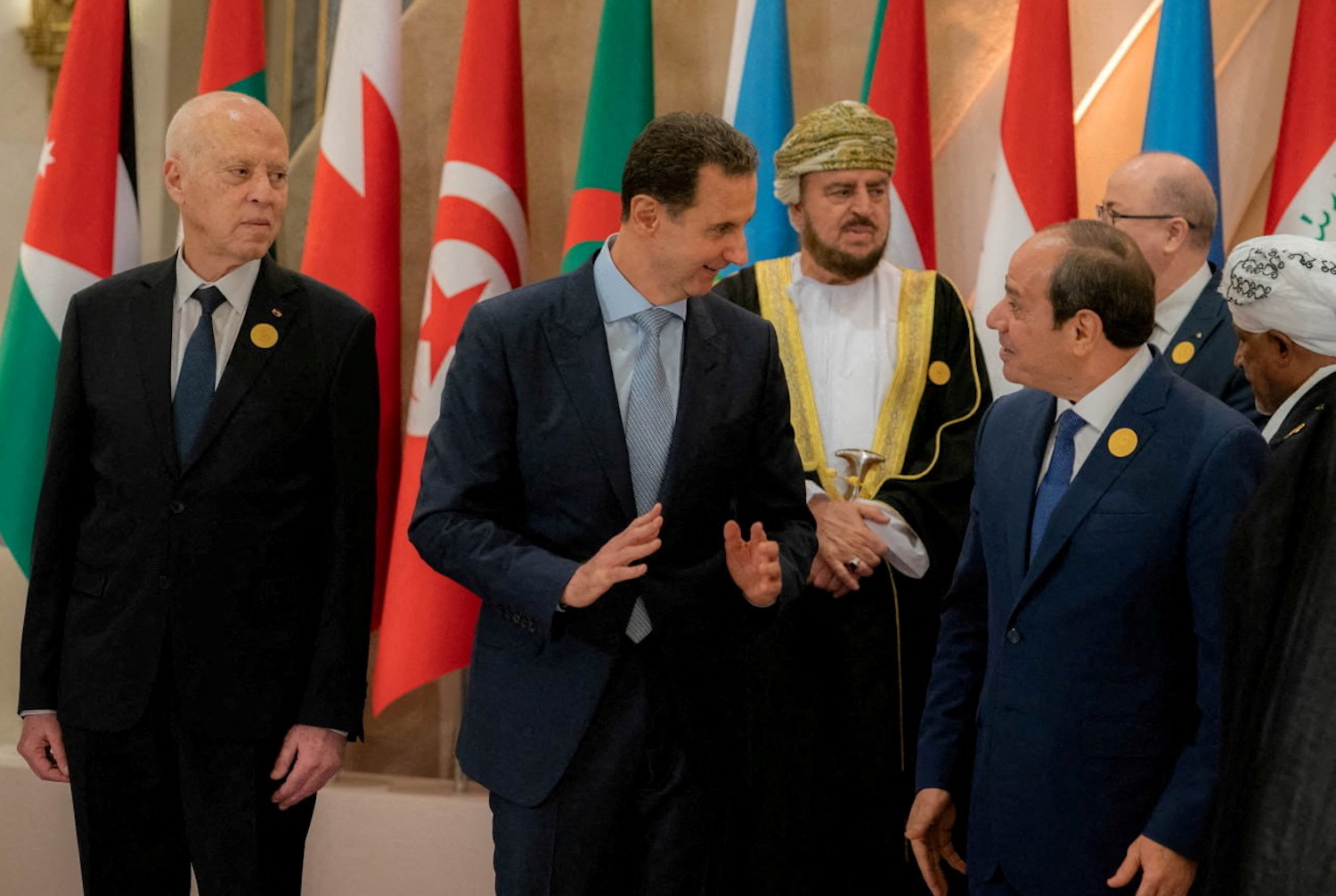

At the Arab League summit in May, Syria was readmitted to the organisation after a 12-year hiatus. Only a few years earlier, rich Arab monarchies had backed the Syrian opposition in its attempt to overthrow President Bashar al-Assad. Now these same leaders are normalising relations with al-Assad. Damascus' emergence from political isolation will have far-reaching consequences that will be felt not only in Arab capitals but also in Moscow, Tehran or Washington. How does Syria's escape from regional isolation relate to the issue of Arab 'strategic self-reliance'?

How has al-Assad survived 12 years of civil war?

Bashar al-Assad became president of Syria by accident. His father, Hafez al-Assad, who had ruled Syria since 1970, had no significant political plans for Bashar. In fact, Hafez chose his eldest son, Bassel, as his successor.

But when Bassel died in a car accident in 1994, Bashar - then working as an ophthalmologist in a London hospital - had to return to Damascus, where his father began to introduce him to the country's political life. Without Bassel's death, Bashar would probably never have become president of Syria and would have continued to work as an ophthalmologist in Europe.

Bashar al-Assad as a doctor (left in the second photo)

The circumstances under which the young Bashar came to power, as well as his very calm nature, meant that when the Arab Spring protests began to sweep across the Middle East region in late 2010 and early 2011, many observers wrote the young al-Assad off, claiming that he was too weak. He was destined to share the fate of Mu'ammar Gaddafi or Hosni Mubarak, who lost their power - and in the case of Gaddafi, his lives - as a result of the Arab Spring.

al-Assad's chances of survival seemed increasingly slim as the street protests turned into a fierce civil war, with opposition groups receiving massive financial and material support from abroad. The Americans armed the rebels with anti-tank rocket launchers. The Turks poured tonnes of equipment and men across the border, and there was a flood of financial support for the rebellion from the Gulf Arab monarchies. To make matters worse, the Kurds declared their obedience to Damascus and large parts of the country came under the control of Islamic State militants.

Bashar's downfall seemed only a matter of time. But to the surprise of many, the young al-Assad held on to power. Crucial to al-Assad's success was securing support from two directions: Tehran and Moscow. From the first months of the civil war, Iran sided with al-Assad and began sending weapons, Iranian trainers and Shia fighters from Iraq, Lebanon and Afghanistan to Damascus.

The balance of power finally tipped in al-Assad's favour in late 2015 when the Russians began their military intervention in Syria. The appearance of Russian air power in Syrian skies was the game changer that allowed al-Assad to retake Aleppo, push the rebels out of Damascus and reach the waters of the Euphrates.

al-Assad survived, but did he won?

Today, after 12 years of civil war, President al-Assad's position is secure. Most rebel groups have been crushed, while Islamic State fighters have been driven into the Syrian desert. al-Assad has survived. But can he be called the winner of the civil war?

The answer is not so obvious. al-Assad does not control the whole country. The remnants of the Syrian rebellion still run Idlib province. al-Assad cannot use force against them because the Turkish army occupies the border areas of Idlib province. Idlib isn’t the only place where Turks are an big problem for al-Assad. The Turkish army also controls much of northern Syria, including towns such as Afrin, Al-Bab, Jarabulus and Tall Abjad.

The country's northeast, where the Syrian Kurds have established their quasi-state, also remains outside al-Assad's control. All attempts to reach a compromise with them have failed. The Kurds are in a very strong negotiating position because US troops are stationed in the areas they control. The American presence, however symbolic, is an effective deterrent to al-Assad (as well as the Turks) from resolving the 'Kurdish question' by force.

The US is also a problem for al-Assad in southern Syria, where it controls the Al Tanf border crossing on the border between Syria, Jordan and Iraq, blocking the shortest land link between Damascus and Baghdad.

The aid from Russia and Iran helped al-Assad to stay in power and, perhaps, to stay alive. But it was not cost-free. Damascus became dependent on economic aid from its 'partners'. A whole network of Iranian military bases and training centres for Shia militias was set up in Syria. Damascus also became a central hub for the smuggling of Iranian weapons into Lebanon, providing a pretext for regular Israeli air strikes on Syria.

Meanwhile, the Russian presence in Syria has led to tighter Western sanctions. In 2020, the so-called Caesar Act came into force, de facto blocking Damascus' ability to receive foreign financial support for the country's reconstruction. The then US special envoy for Syria, James Jeffrey, summed up the purpose of US policy as follows: "This isn't Afghanistan, this isn't Vietnam. This isn't a quagmire. My job is to make it a quagmire for the Russians"

Why do the Arabs want to normalise relations with al-Assad?

The Arab monarchies prominently supported the rebels, hoping for al-Assad's swift demise. Why did they decide - after 12 years - to normalise relations with Damascus and reinstate Syria as a member of the Arab League?

Above all, the Arabs realised that the rebellion they supported - would not remove al-Assad from power. This became especially clear after 2015, when the Russians intervened on al-Assad's side. The United Arab Emirates was the quickest to adapt to the new reality, and as early as 2018 (along with Bahrain) resumed official diplomatic relations with Damascus.

The Emirates has become one of the most prominent supporters of Syria's reintegration into the Arab League. UAE diplomats have been lobbying on al-Assad's behalf both in Washington and in Arab capitals.

The Emirates warned that Arab inaction on Syria would lead to al-Assad's continued dependence on aid from Tehran, which in turn could strengthen the pro-Iranian bloc across the region. Moreover, Abu Dhabi argued that normalising relations with al-Assad would help block Turkey's expansionist ambitions, which the Arabs view with great suspicion.

Emirati diplomatic efforts were relatively well received in Arab capitals. Still, in the end al-Assad's plan to return to the 'Arab community’ failed, because the Americans opposed it - most notably through the Caesar Act, which allowed sanctions to be imposed on any country providing economic aid to al-Assad's government.

As a result, Arab enthusiasm for normalising relations with al-Assad waned, and the issue was not revisited until early 2023. However, the driving force behind this process was not the efforts of Emirati diplomacy but the wider regional realignment.

al-Assad and Mohammed bin Zayed (then heir to the Abu Dhabi throne and now president of the UAE), al-Assad's visit to the Emirates, March 2022.

al-Assad and Mohammed bin Zayed (then heir to the Abu Dhabi throne and now president of the UAE), al-Assad's visit to the Emirates, March 2022.

Arab strategic self-reliance

For some years now, the Arab monarchies, and Saudi Arabia in particular, have been pursuing an increasingly independent foreign policy. Individual Saudi decisions are often mistakenly seen in the context of the global rivalry between the US, Russia and China. In reality, however, Saudi Arabia's actions under the de facto leadership of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) are primarily aimed at strengthening the kingdom's strategic independence. The Saudis are not looking to move closer to China, Russia or the US but to strengthen Riyadh's role as an autonomous decision-making centre.

Saudi policy is not unique in the region. The United Arab Emirates, for example, is pursuing very similar policies, also aimed at strengthening its own strategic independence.

The strengthening of Arab strategic self-reliance accelerated especially after 24 February 2022, when America became involved in supporting Ukraine, and the Middle East became a tertiary theatre for Washington.

Arabs have lost faith in the effectiveness of US diplomacy. In Arab capitals, US policy towards Iran and its regional partners has been particularly misjudged. Although President Trump withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal in 2018 and sanctioned virtually all sectors of the Iranian economy, this did not force Tehran to make any concessions. Hardly any sanctions have been able to reduce Iranian influence in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon or Yemen.

In this situation, the Saudis decided to take matters into their own hands. In March 2023, during a meeting in China, the Saudis signed an agreement with the Iranians to normalise relations. A few weeks later, the Emirates - accusing the US of passivity in the face of Iranian attacks on merchant ships - withdrew from the international coalition that was supposed to guarantee the security of Gulf waters.

Syria is yet another example of a crisis that Arab leaders are trying to resolve themselves - even if it means 'straining' relations with Washington.

The atmosphere for a compromise with al-Assad was all the better because the Saudi-Iranian agreement - concluded in China in March - had caused a general relief in the region. In addition, a major earthquake that struck Turkey and Syria in February, killing some 59,000 people, contributed to the process. Coordinating humanitarian aid to Syria allowed Arab countries to reopen communication channels with Damascus.

It was in this atmosphere that the Saudi foreign minister flew to Damascus in April for the first time in 12 years and handed al-Assad an official invitation to this year's Arab League summit in the Saudi city of Jeddah.

Bashar al-Assad and Prince Faisal - Head of the Saudi Foreign Ministry

Bashar al-Assad and Prince Faisal - Head of the Saudi Foreign Ministry

Moscow view, Tehran view

Syria's return to the Arab League is a success not only for al-Assad but also for Moscow. For years, the Russians have been trying to normalise relations between Syria and the Arab monarchies. Moscow can therefore portray Syria's return to the League as a success achieved thanks in part to Russian diplomacy. This is of particular PR importance at a time when Russia itself is politically isolated due to its invasion of Ukraine.

al-Assad's other ally, Iran, is less enthusiastic about Syria's return to the Arab League. Indeed, the Iranians have been trying to turn Syria into their 'protectorate' since the beginning of the civil war. Although Tehran has gained enormous influence in Syria, its attempt to subjugate Damascus completely has failed. This was due to the cunning of al-Assad himself, who manoeuvres smoothly between Moscow and Tehran and thus retains a degree of independence.

Now that Syria has returned to the Arab League, it is likely that the Arab monarchies will do all they can to undermine the Iranians' position in Syria further. A complete break between al-Assad and Iran is out of the question. Still, the stability of Syrian-Iranian cooperation will undoubtedly be tested - especially as the Iranians have already had doubts about al-Assad's loyalty to Tehran.

al-Assad and Iranian President Raisi

al-Assad and Iranian President Raisi

Consequences of Syria's return to the Arab salons

But Syria's reinstatement as an Arab League member is only the first step on al-Assad's path out of political isolation.

It is worth remembering that Syria's return to the Arab League does not even imply an automatic normalisation of relations between Syria and all the member states of the association. Qatar, for example, did not block Syria's return to the club but at the same time announced that it did not intend to normalise relations with Damascus.

Until al-Assad reaches a compromise with the Syrian Kurds and the Turks, his legitimacy to rule the country will continue to be questioned by some countries. The protectiveness with which the Americans have surrounded the Kurds effectively rules out the possibility of a settlement with Damascus. Normalising relations with the Turks appear easier - President Erdogan has already signalled his willingness to meet with al-Assad in late 2022. However, Ankara and Damascus have very different visions of what such normalisation should look like. al-Assad hopes for a complete withdrawal of Turkish troops from Syria. Erdogan, on the other hand, wants to rid Turkey of some 3.5 million Syrian refugees and create a buffer zone on the border that would separate Turkey from Syrian Kurdish settlements.

Still, the biggest obstacle for al-Assad remains US sanctions and the aforementioned Caesar Act, which Donald Trump signed into law in 2019. This was a landmark act, as previously, the Americans had mainly imposed sanctions on Damascus individually, targeting al-Assad and his closest associates. Instead, the Caesar Act required the US Treasury Department to impose sanctions on any entity providing "significant" financial, material, or technological support not only to the Syrian government but also to military trainers, mercenaries, and fighters operating in Syria on behalf of Russia and Iran.

Significantly, on the basis of the Caesar Act, the US administration has also developed a special strategy to block the participation of 'foreign actors' in the reconstruction of the country from war damage - in areas controlled by al-Assad, the Russians or the Iranians.

In practice, Caesar's Law means that the wealthy Gulf monarchies (such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia) - although interested in financing the reconstruction of Syria, seeing it as an opportunity to reduce Iranian influence - will not be able to do so. If the Arabs help financially to prop up Syria, they themselves will be subject to US sanctions.

It is reasonable to assume that the Arabs - through a web of shady connections - will probably find a way around some of the sanctions, and limited financial aid will flow to Damascus. However, such transfers will be difficult and are likely to remain a drop in the ocean of Syrian needs. Indeed, the World Bank estimates that rebuilding Syria will cost between $250 billion and $1 trillion.

In theory, the Caesar Act is a 'temporary law' that will expire in 2025. But as soon as al-Assad was invited to the Arab League summit, a so-called 'anti-normalisation bill' appeared in the US Congress. It would extend the Caesar Act until 2032 and tighten sanctions against Damascus. In addition, the bill would require the US State Department to develop a special strategy to prevent other countries from further normalising relations with al-Assad, thus ensuring Syria's continued isolation on the international stage.

al-Assad at the Arab League summit

al-Assad at the Arab League summit

Syria - the case for strengthening "Arab strategic independence

Nevertheless, Syria's return to the Arab League is of essential importance. It is a clear signal from the "Arab community" that it can accept al-Assad as Syria's president and of resetting relations with him - even if it means a "scratch" in US-Arab relations. But this is only the first step towards ending Damascus's political isolation. The existence of US sanctions means that the benefits al-Assad can derive from returning to the Arab League will be very limited.

The disagreement between America and its Arab allies over Syria is a good illustration of the broader problem of "Arab strategic independence". Syria is an ideal starting point for discussing the US position in the Middle East. Arab leaders see US policy towards the region as less and less effective and are trying to solve Middle Eastern problems independently. Syria is not an exception, but a certain regularity. Despite American objections, the Arabs continue cooperating with Russia in OPEC+, the Emirates are helping the Russians circumvent Western sanctions, and the Saudis are normalising relations with Iran - symbolically signing an agreement in China.

The problem of "Arab strategic independence" stems from the high ambitions of the new generation of Arab leaders, as well as from America's diminished activity in the region, which has replaced the Middle East with rivalry with Russia in Europe and with China in the Pacific.

The assertive policy of the Arabs is often misunderstood by Western commentators who try to assess the next moves of the Saudis or Emiratis in the context of the global competition for influence between Washington, Moscow and Beijing. As a result, there are often alarmist warnings in the West about the imminent collapse of the US-Arab alliance. But the truth is less sensational.

The Arabs value America's military support. No other country in the region - be it China or Russia - can replace the Americans as the protector of Arab countries and the guardian of freedom of navigation in the Persian Gulf. The Arabs do not want to break the alliance with America. Still, they are increasingly calling for a revision of the principles on which it is based, which ultimately undermines the US position in the region.

The truth is that American policy towards the region is going through a period of deep crisis. Washington itself is largely to blame. For years, the Americans have not proposed a coherent formula for cooperation between the countries of the Middle East. Indeed, in Trump's time the idea of an "Arab NATO", a confrontational policy towards Iran and the so-called "Abraham Accords" to end the Arab-Israeli conflict have come to the fore.

al-Assad and Mohammed bin Salman

al-Assad and Mohammed bin Salman

Yet the "Trump proposal" for the Middle East was short-lived. When Joe Biden took over the White House, US policy towards the region also changed. The new administration tried to withdraw from the confrontation with Iran. But negotiations to return to the 2015 nuclear deal failed, and the region fell off Washington's list of priorities. The Middle East is now a third-tier theatre for Biden, with Europe and the Pacific higher up the hierarchy.

As long as the Americans do not offer the Arabs a new, coherent formula for cooperation, the Arabs will develop "strategic independence", create their own foreign policy and try to redefine their alliance with the US. This, in turn, will be a source of constant, recurring tension between Arab capitals and Washington, as exemplified by Bashar al-Assad's re-emergence in the Arab diplomatic chessboard.